Introduction

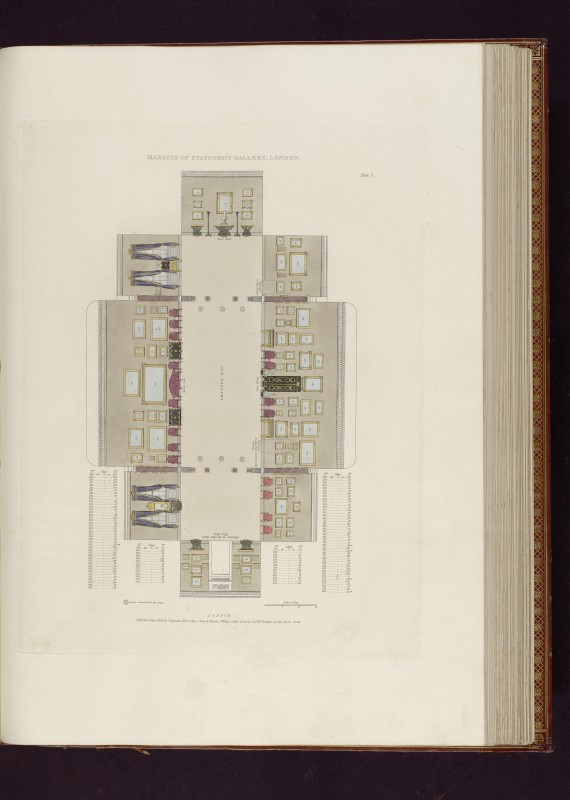

John Roffe (engr.) after Charles Heathcote Tatham (arch.), The Marquis of Stafford’s Gallery at Cleveland House. Plan of the Suite of Rooms on the first floor, in John Britton, Catalogue Raisonné of the Pictures Belonging to the Most Honourable the Marquis of Stafford, in the Gallery of Cleveland House (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1808), 23 cm Digital image courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut, N5245 S75

Figure 1.

In keeping with its illustrious reputation, Cleveland House was celebrated in a variety of publications, including a widely circulated guidebook written by the antiquarian John Britton, printed in 1808, and a four-volume illustrated catalogue raisonné assembled by William Young Ottley, printed in 1818. Though they differ in significant respects, both Britton and Ottley’s catalogues were elaborate and ambitious attempts to record the quality and depth of Cleveland House’s collection of art.4 Britton’s book, though small in size and likely intended to be carried while walking in the gallery, provided a laudatory introduction to the gallery, extensive notes on the pictures from the Italian and French schools, as well as a floor plan and view of the New Gallery, the largest of the gallery’s twelve rooms. By contrast, Ottley’s effort was a folio-sized catalogue raisonné, illustrated with colour plates, and bound in Russia leather for the enormous sum of £178 10s.; this luxurious edition was clearly intended to proclaim the collection’s significance on the national, and international, stage.5 Despite their differences, both adhered to a set of established conventions for catalogues and guidebooks of aristocratic collections produced in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.6 They emphasized the most prestigious pictures from the Italian and French schools, particularly those from the Orleans Collection, and praised the Marquess of Stafford for his “patriotic zeal” and “noble” example.7 The authors of catalogues and guidebooks assumed that their audience was the educated and polite public and that their purpose was to celebrate the collector’s magnanimity in making his house and pictures available to members of this group.

In 1812, however, an idiosyncratic project upended these assumptions. William Cantrill, a porter in the employ of the Marquess and Marchioness of Stafford, dedicated a privately printed book of etchings to her ladyship titled Etchings from Original Pictures in the Cleveland-House Gallery. Consisting only of a title page, dedication, and six etchings, it stands out not only for its modesty but for its unusual choice of pictures from the collection—Netherlandish and French genre paintings.8 Passing over the Italian and French mythological, religious, and historical paintings that dominated both the physical spaces of the gallery and its public reputation, Cantrill instead offered readers a narrow subset of “subject” pictures, scenes of daily life, and animals. His choice of pictures should remind us that the “lesser” schools and genres were just as amply represented in the collection as their Italian and French counterparts. Of the 229 paintings on display at Cleveland House in 1806, more than half came from the northern schools of art, which were represented by such esteemed names as Rembrandt, Rubens, Ruisdael, and Cuyp, in a range of genres from religious subjects to landscape and still life. The gallery’s 138 “northern” pictures were densely hung in elaborate, nearly symmetrical patterns in a very large room designated as the Old Gallery, which was abundantly furnished with suites of Oriental and upholstered furniture. In most catalogues, these paintings barely warrant a mention; in Cantrill’s they are the exclusive focus, though he offers no explanation or justification for his selection.

As if confirming Cantrill’s unconventionality in focusing on small subject pictures, the catalogue departs in almost every way from the template established by other catalogue writers of the period. The etchings, attributed to Cantrill, are clearly the work of an amateur. Although slim and light, the catalogue is nevertheless too large to be comfortably used while strolling through the gallery, conforming neither to the expectations of a guidebook nor to the genre of catalogue. It is neither comprehensive nor lavishly presented. It contains no laudatory essay nor scholarly apparatus. Intriguingly, while most catalogues of the period were offered as tributes to the patriotic and public-spirited nature of their male owners, Cantrill’s is dedicated to “Her Ladyship”, the Marchioness. The catalogue is presented as a private, personal homage to a benevolent mistress, rather than as an intellectual or patriotic undertaking. In keeping with its somewhat mysterious origins, few copies survive in public repositories. One, illustrated here, was presented to the Society of Antiquaries in 1812 by a distant relation of the family; another is in the collection of the British Museum.

By virtue of its remarkable difference from other catalogues made of important art collections in this period, the Cantrill catalogue (if that term even adequately describes it) may appear to be little more than a charming curiosity. Yet its eccentricity presents an opportunity to consider the Cleveland House gallery afresh, in particular to reflect on the role that the Netherlandish pictures played in shaping both the collection’s identity and visitors’ reactions to it. Despite being glossed over by authors like Britton and Ottley, Netherlandish genre painting had become quite fashionable in the early nineteenth century amongst collectors, the general public, and artists, although its popularity sometimes sat awkwardly with its tendency to depict “everyday life” (which, as David Solkin has noted, can be read as a gloss for “lower-class life”) without the veneer of politeness or middle-class morality that audiences preferred.9

Why, then, these pictures? What purpose could such an idiosyncratic tribute to the Marchioness and to Cleveland House serve? In this article, I will argue that Cantrill’s publication is much more than a haphazard assemblage of little-known subject paintings, and that instead, it can be read as a narrative assembled from pictures hanging in Cleveland House. This narrative, I will suggest, can be “read” like a wordless story in pictures centring on the virtues of village life, the miseries of poverty, and the possibility of redemption at the hands of a female benefactress, creating not only a narrative, but also a thematic connection between pictures which would not otherwise exist.

Cantrill’s catalogue was timely, and at its heart, carried a moral. At the time the book appeared in 1812, the Marquess and Marchioness had been undertaking improvements on the Marchioness’s hereditary estates in Scotland for some years; these were part of a series of controversial land-management decisions which have become popularly known as the Highland Clearances. The Marquess and Marchioness’s names became irrevocably associated with the controversy, and widespread condemnation of their actions appeared in the Scottish and metropolitan press. In 1819 the poet Robert Southey wrote: “There is at this time a considerable ferment in the country concerning the management of the M. of Stafford’s estates: they comprise nearly 2/5th of the county of Sutherland, and the process of converting them into extensive sheep-farms is being carried on. A political economist has no hesitation concerning the fitness of the end in view, and little scruple as to the means.”10 Once set in motion, the controversy surrounding the Highland Clearances persisted for decades—Karl Marx invoked the Clearances as the example par excellence of the triumph of “capitalistic agriculture”11—and was revived in 1963 with the publication of John Prebble’s popular history, The Highland Clearances, a polemical and highly emotional account that portrays the Staffords as members of a greedy aristocracy with a near-genocidal mania to replace human tenants with sheep.12 More recently, the economic historian Eric Richards has published numerous books examining the complicated finances of the Leveson-Gowers and the subtle interrelationships between their canal and railroad holdings and the Highland properties as both sources and sinks of wealth.13 Despite the international notoriety of the Clearances, however, no art historian has considered the Leveson-Gowers’ role as patrons and collectors in the context of their activities in the Highlands.14

Cantrill’s book provides an opportunity to connect and reinterpret the history of the gallery and of the Clearances and examine how they inflected one another. By reproducing only a handful of pictures from the collection at Cleveland House, the book operates as a form of synecdoche, mobilizing a few carefully chosen examples of subject painting to create a vision of Cleveland House as a repository of small-scale genre scenes that runs counter to its reputation as a collection of important Italian old master paintings. The book’s narrative, drawing upon both the conventions of genre painting and its display, promotes and endorses the notion that the gallery was not merely a space of glamour, but one that stitched together the lives of aristocrats and their tenants, and where empathy and care for dependent people was literally “on display”.

Cleveland House and its context

William Cantrill, Title page, in Cantrill, Etchings from Original Pictures in the Cleveland-House Gallery (London: Published by subscription, 1812), 46.4 x 36.4 cm Digital image courtesy of Society of Antiquaries Library, London

Figure 2.

The collection had already been open to a limited audience in the Duke’s lifetime. To facilitate the continued exhibition of the collection, the Marquess commissioned a renovation and expansion of the gallery and established a ticketing system.16 While the transparency with which this regime was made known to the public (the regulations were published in Britton’s catalogue) theoretically made Cleveland House one of the most accessible spaces in which to view old master paintings in London, in practice those granted admission usually had a personal connection to the Marquess of Stafford’s family or letters of introduction from Royal Academicians. During its first few years a number of writers energetically promoted the idea that the gallery was more than just a private collection of interest to connoisseurs; commentators noted that it was “a National Museum rather than [a] private collection”,17 one which gave “the idea of a national establishment rather than of the collection of an individual”.18 Cleveland House cultivated this image with great success, coming to be regarded as a space with an important role to play in the development of public taste. In order to carry out this function pictures were hung according to national schools, giving priority to the most important Italian historical and religious subjects of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Given the limited public for the gallery, whether it was actually successful in altering public taste is debatable. What is certain is that the act of opening the collection to the public greatly enhanced the reputation of the Marquess and Marchioness of Stafford. Upon the Marquess’s death in 1833, a widely circulated obituary emphasized his “liberal and judicious” patronage, which had “added most materially to the satisfaction of that class of society, whose leisure and education render the improvement of the Fine Arts a principle part of their enjoyment”.19

The Sutherland estates

The Cleveland House gallery appeared, in the eyes of contemporaries, to be the quintessential symbol of aristocratic patriotic benevolence. At the same time, however, its glamorous image stood in stark contrast to that of other properties owned by the family—the small, poorly maintained cottages (Robert Southey used the term “man-sties”) occupied by their Scottish tenants.20 This dichotomy has persisted in art history, where the Marquess of Stafford has been studied primarily for his importance as a patron and collector, with little attention given to the socio-political context of the family’s involvement in important economic developments. Yet, in 1806, the very year the Cleveland House gallery opened to the public, the Marquess and Marchioness undertook a campaign of enclosures and improvements on their estates, marking the beginning of a series of actions that would ultimately rank the family amongst the most controversial landlords of the nineteenth century. The Marchioness of Stafford, who also bore the title Countess of Sutherland in her own right, brought nearly one million acres of northeastern Scotland to her marriage in 1785.21 Known as the Sutherland estates, they were a mixed blessing, as both land and tenants were poor.22 Upon receiving the Bridgewater inheritance, the Marquess and Marchioness quickly took steps to invest in a scheme of “improvement” on the estates intended, at least in part, to ameliorate conditions for the tenantry. Improvement, as employed throughout Britain in this period, meant the consolidation of land: as landlords increased their acreage, smaller farms were absorbed into larger ones in a bid to increase productivity and profitability. An outcome of consolidation was that lands which had traditionally enjoyed common use by villagers became fenced property and subject to modern agricultural farming techniques, a process often referred to as “enclosure”. From the landlord’s point of view, enclosure made land more productive. From the tenant’s point of view, enclosure and related efforts at “improvement” represented the seizure of public property by private, landed interests. The mixture of self-interest and benevolence that characterizes the Sutherland case was therefore not unusual; on the contrary, the improvements planned for the Sutherland estates were born of the landowning classes’ preoccupation with improvement during this period.

Enclosures in the Scottish Highlands, which have come to be known generally as the Highland Clearances, are amongst the most scarring episodes in Scottish history. The euphemistic term “enclosure” smoothed over a process that was often contentious and occasionally violent. In theory, the Clearances were intended to improve the land by converting small farms into large grazing fields for sheep and removing the impoverished tenants to the coast, to pursue fishing and other occupations as a more economically viable way of life. In practice, however, many Highlanders violently resisted the changes, in which they had no say. Local people, many of whom were left unemployed, hungry, and uprooted from their communities, were angry at the methods undertaken by landlords to effect change on the Highland estates, and anger quickly turned to violent resistance in the form of rick-burning and related means of protest.23 Many of those who refused to accept the schemes emigrated to Australia, Canada, and the United States; much of the worldwide Scottish diaspora today can be traced to these events.

Gossip, pamphlets, and articles circulated criticizing Highland landlords for their greed and heavy-handed tactics, or for both. By the 1810s, observers were making a more explicit connection between the effect of the Clearances on the poor, and the expensive, cosmopolitan lifestyle pursued by their London-based landlords. In 1819 the New Monthly Magazine delivered a crushing assessment: “When all is amassed that law and threats of displacement can procure, the parties enriched leave the parties impoverished, to squander their earnings and to forget their woes amid the luxuries of the metropolis.”24 Even as these events were underway, it is clear that the family’s growing reputation as patrons of the arts helped deflect criticism. For example, agricultural reformer Thomas Bakewell, no fan of landowners who mistreated their dependants, raised the possibility that the Marquess’s reputation as “a highly esteemed nobleman . . . who is the general arbiter of taste in one of the fine arts” somehow provided an alibi for alleged unethical acts toward his tenants.25

Reading Cantrill

William Cantrill, Dedication page, in Cantrill, Etchings from Original Pictures in the Cleveland-House Gallery (London: Published by subscription, 1812), 46.4 x 36.4 cm Digital image courtesy of Society of Antiquaries Library, London

Figure 3.

Cantrill’s dedication does not downplay his lack of professional credentials; in fact, he points out that the etchings are “first attempts from an untutored hand”. A comparison of one of the etchings to the painting on which it is based, Antoine Le Nain’s The Village Piper (now in the Detroit Institute of Arts) (figs. 5 and 6), supports this assertion.26 While faithful to Le Nain’s composition, Cantrill’s etching is an ungainly translation of the painting’s sensitively rendered flageolet-player and listening children. In contrast to Le Nain’s picture, which situates the figures within a deftly suggested darkened and ambiguous picture space, Cantrill’s figures float on an empty white page, given depth only with awkward hatching suggesting shadows near the feet of the girl and boy towards the right-hand border of the image. The worn and patched clothing depicted in Le Nain’s painting creates an atmosphere of pathos that contributed to the painting’s appeal to nineteenth-century viewers. Cantrill copies the clothing in his etching but without capturing its scrupulous attention to detail, despite the fact that Cantrill’s reproduction is larger than the original painting, which measures only 22.5 x 30.5 cm. For example, the thread trailing from the shirt of the boy in the red cap is indistinct in Cantrill’s reproduction.

The very clumsiness of the etchings, however, lends them an air of unpretentiousness. By assuming the perspective of a humble, even unsophisticated, viewer, the catalogue may have held a special appeal to the Marchioness and the book’s other “readers”. Cantrill’s explicitly identified status as a domestic servant highlights the potential social and moral benefits of the gallery as an agent of working-class improvement. In general, domestic staff were not included in the polite and artistic crowds granted official tickets to the open days at the Cleveland House gallery, though they were present—as attendants dressed in uniform or in service at parties. While they thereby had access to works of art, they were excluded from circulating amongst the elite visitors to whom printed tickets were issued and could not have enjoyed many opportunities to glance at the pictures while carrying out their official duties. We can only surmise that the Marchioness herself encouraged Cantrill to demonstrate his affection and support for her by testing his artistic potential in this way; in turn it was almost certainly she, or her husband, who secured the funding necessary for printing this book.

Cantrill’s role as a porter placed him a unique position in relation to the gallery’s spaces, and provides an intriguing clue as to his relationship to the art displayed there. In general, a porter was a person responsible for opening the door to a house, a role particularly important in urban townhouses where visitors came and went on a regular basis.27 As such, porters in these houses were both literal and symbolic gatekeepers, monitoring, granting, or refusing access to the interior of the house. The open days at the gallery at Cleveland House represent a complicated variation on the typical duties of the porter. Cleveland House was notionally open to the public during viewing hours, yet in practice the list of people given access was closely monitored. It was the porter who was entrusted with the responsibility for managing the list of people who were to be given access to the gallery on open days—Britton tells us that applications to enter the gallery were “inserted in a book by the Porter, at the door of Cleveland-House, any day except Tuesday; when the tickets are issued, for admission on the following day”.28 While I have found no explicit evidence that Cantrill was in fact the same porter given responsibility to keep the book of applications to enter the gallery, in light of the publication of his etchings it seems likely that he was the porter who occupied this position in 1812. As a member of the working classes normally excluded from the gallery’s rarified list of attendees, Cantrill nevertheless had access to and responsibility for managing both the inclusion and exclusion of visitors. As such, he needed to understand who would qualify for access and act as a conduit for his employer’s assumptions about social class.

Cantrill’s position as a porter at Cleveland House and as an amateur artist encouraged by his employers suggests that the images in his catalogue may have been chosen to represent the values that a mistress and her “grateful, and dutiful” servant were expected to share. In order to elucidate this, we should study these pictures as a contemporary “reader” may have done, in the order in which they appeared. By virtually “reading” the book, a narrative emerges that puts on display both the picturesque and the undesirable aspects of poor, rural life, before offering the possibility of redemption. Such a reading suggests the ways in which subject painting was particularly well suited to constructing a narrative that could be understood across the boundaries of social class separating Cantrill and the ostensible audience for this book.

Figure 4.

William Cantrill after David Teniers the Younger, Boors Playing at Cards, in Cantrill, Etchings from Original Pictures in the Cleveland-House Gallery (London: Published by subscription, 1812), 46.4 x 36.4 cm

Digital image courtesy of Society of Antiquaries Library, London

As we turn over the dedication page, the first image we encounter is an etching after David Teniers’s Boors Playing at Cards (fig. 4). This image depicts the interior of a pub, with a group of men gathered around a half-barrel which has been pressed into service as a card table. Two other men smoke while a dog looks out from the right-hand corner. The picture, as interpreted by Cantrill’s etching, exhibits many of the characteristics stereotypically associated with genre scenes—lower-class people at their leisure, drinking and playing cards in a humble setting. Scenes like these, executed with great charm and a high level of finish, made Teniers one of the early nineteenth century’s most beloved and eagerly collected Flemish subject painters (not to mention the most valuable). Given the ample selection of pictures by Teniers available in the Staffords’ collection, it is unsurprising that half of Cantrill’s etchings were based on works attributed to him. All three are typical examples of Teniers’s art, demonstrating picturesque qualities of variety, roughness, and attention to detail. Though the original picture after which Cantrill’s engraving was made is in a private collection, a tavern scene by Teniers in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington exhibits similar characteristics. In this version, the tavern is populated with men playing cards, drinking, snoozing, and urinating in a darkened corner—though Cantrill’s etching, and presumably, the Cleveland House original, includes no such urinating figure (see David Teniers the Younger, Tavern Scene, 1658, and, from much earlier in his career, Teniers the Younger, Peasants in a Tavern, ca. 1633).

Cantrill’s catalogue continues with two further subject paintings depicting common life. Turning the page, we find Antoine Le Nain’s The Village Piper (figs. 5 and 6), which depicts a group of poor but healthy youngsters gathering around a musician. The third plate, Teniers’s Ducks in the Water (fig. 7), exhibits more of the artist’s renowned charm by adapting the conventions of genre to animal painting, as a female duck and ducklings turn their necks to admire the plumage of their male companion. Taken as a group, the first three images, all of which in some way relate to village or family life, demonstrate the qualities of northern European genre paintings that made them beloved by British audiences in the period. Subject pictures typically offered urban viewers a picturesque and comforting view of the rural way of life that traditionally had underpinned the wealth of landed families like the Staffords. Teniers’s family of ducks occupies a peaceful corner of a pond, suggestive of the natural order of social hierarchies as of benefit to all. As Sarah Monks has written, such works appealed to British viewers who wished to believe in their “apparent revelation of nature’s aesthetic and social harmoniousness”.29 Similarly, Le Nain’s image of poor youngsters (or in John Britton’s words, “a group of five ragged children”) gathering around a village musician may have conjured up an image of Lord and Lady Stafford’s own tenantry, who relied upon their landlords’ goodwill for their continued prosperity.30

At this point Cantrill introduces an image that appears to disrupt the narrative. Jan Fyt’s Starving Dog (fig. 8)31 depicts a chained dog whose plate of food is just out of reach; the chain pulled taut, the dog appears unable to reach the crust of bread that has been tossed into his bowl, his tongue lolling out of his mouth in hunger. The image introduces an unsettling element into a sequence that heretofore was suggestive of relaxed comfort and harmonious social relations. The dog is chained to a small door on the interior of what appears to be the gatehouse of an immense estate. In the background an urn containing a small tree perches on the edge of a low stone wall topped by a decorative coping. The impression is of a grand dwelling just out of sight.

Figure 8.

William Cantrill after Jan Fyt, The Starving Dog, in Cantrill, Etchings from Original Pictures in the Cleveland-House Gallery (London: Published by subscription, 1812), 46.4 x 36.4 cm

Digital image courtesy of Society of Antiquaries Library, London

Fyt’s picture seems an unlikely choice for a catalogue whose intent is to honour an aristocratic lady. The Starving Dog suggests the neglect of a dependent creature by a careless master or mistress; an alert viewer might have been reminded of the distress of the Highland tenants, their homes and livelihoods in a state of upheaval as a result of Lord and Lady Stafford’s improvements. Stories that circulated about the Clearances, both at the time and during subsequent decades, frequently made recourse to the notion that the tenantry had been treated like animals; a woman named Betsy MacKay, who was sixteen when her family was evicted in 1814, recalled much later, “the people were driven away like dogs who deserved no better, and that, too, without any reason in the world.”32 Stories like this one caused widespread outrage. From this perspective, Cantrill’s use of Fyt’s picture might be interpreted as subversive, emphasizing rather than rebuffing the possibility that Lord and Lady Stafford were not the benevolent landlords they purported to be.

Figure 9.

William Cantrill after David Teniers the Younger, Farm Houses and Boors, in Cantrill, Etchings from Original Pictures in the Cleveland-House Gallery (London: Published by subscription, 1812), 46.4 x 36.4 cm

Digital image courtesy of Society of Antiquaries Library, London

However, this suggestion is undone when we turn the page. Teniers’s Farm Houses and Boors (fig. 9) offers a palliative to The Starving Dog, depicting the tidy dwellings of a small farm and villagers at play.33 At the centre of the picture a woman bearing a platter of food is shown making her way through a doorway. The sustenance that her offering implicitly provides pulls together the disparate elements of the picture—one man urinating immediately to the woman’s right, other men playing nine-pins scattered across the foreground.34 David Solkin has astutely observed that a common device in Teniers’s pictures is the “way in which his figures tend to be arranged into groups or individuals who remain resolutely separate from one another, their dispersal acting as a spatial sign for the aimless nature of their daily existence”. This aimlessness exhibited by the playing and urinating men might be interpreted as another way of describing the sloth or “idleness” that the upper classes assumed was endemic to the Highlanders—a lack of motivation which had been invoked as a justification for improvements and clearance in the first place. The arrival of a benevolent female figure transforms the story from one of starvation to contentment, aimless wandering to productivity. Binding together the composition, she improves the lives of the tiny figures who inhabit it. Appearing at this point in the catalogue’s narrative, this figure could be interpreted as a substitute for the Marchioness, so as to cast her attention to the needs of the Highlanders in a positive light.

As if to emphasize the point, Cantrill ends his catalogue with a final interior scene which focuses the viewer’s attention on a moral female figure, in Quirijn van Brekelenkam’s Returning Thanks (fig. 10). We turn the page to find a woman praying at a small table in a simple domestic interior. Her hands clasped and eyes closed, she presents an image of piety, grateful for the loaf of bread on the small table before her. Brekelenkam was known for his prolific production of small-scale paintings of “virtuous elderly women”, which typically featured female figures in simple dress, eating plain meals of bread or soup, in demonstrably poor surroundings.35 A viewer considering Brekelenkam’s image within the framework of Cantrill’s catalogue might see the woman as a Highland tenant, grateful to a benevolent mistress for the tidy house and ample food to which she now has access. The representation of a pious woman could simultaneously burnish the reputation of the Marchioness by associating her name with an image of industriousness, wisdom, and gratitude. Returning Thanks thereby emphasizes the notion of a mutually beneficial relationship between superiors and dependants that the Marchioness seems to have been at pains to establish.

Figure 10.

William Cantrill after Quirijn van Brekelenkam, Returning Thanks, in Cantrill, Etchings from Original Pictures in the Cleveland-House Gallery (London: Published by subscription, 1812), 46.4 x 36.4 cm

Digital image courtesy of Society of Antiquaries Library, London

Serving as a transition between images of peaceful village life and those of improvement and contentment, The Starving Dog’s position at the midpoint of this catalogue represents a pivotal moment in the development of its narrative and the ideological message it carries. The inclusion of The Starving Dog acknowledges the rumours about the Marchioness’s lack of compassion for her tenants, and serves as a moment of transition. The images in Cantrill’s catalogue present this story, then turn to images which seem to suggest the benefit of female intercession on behalf of the people. Following the image of extreme suffering represented by The Starving Dog, the nadir of a downward slide into hunger and desperation, the sequence of images ends with two pictures which both rely upon the imagery of women’s intervention, both material and spiritual, to improve the condition of humanity.

Considered as a whole, the selection of pictures and the narrative structure imposed by their ordering within the book invited viewers to reflect upon the peaceful and harmonious rural life that the processes of enclosure and eviction were intended to create, as opposed to the chaotic and violent one they had set in motion. Turning the pages as Cantrill’s readers might have done, the sequence of images tells the story of lower-class life and of its amelioration through benevolence and philanthropy. The lowly nature of the images presented in Cantrill’s catalogue also draws a sharp contrast with the Marchioness’s reputation for lavish living, associating her with humble virtues and deflecting attention from the controversial treatment of her tenants. Images of poor but contented rural folk, such as those featured in the first three images, who are then struck by neglect and starvation, reproduces the aristocratic understanding of Highland history in pictorial form.

Looking at subject pictures in the Cleveland House gallery

The narrative reading of Cantrill’s book that I have proposed functioned as an alternative to interacting with and looking at genre pictures within the physical, intellectual, and pedagogical frameworks offered by the gallery itself. The book, by imposing a viewing order, and bringing the pictures into close proximity to the reader, permitted a re-framing and re-purposing of pictures which in the gallery played secondary roles in the arrangements of pictures on the wall. How then, did Cantrill’s catalogue shift the terms of looking at the pictures it chose to represent? One of the book’s most meaningful interventions in the relationship between picture and viewer was to bring small genre scenes, several of which were tiny to begin with, down from the walls and to place them in the viewer’s hands, offering an opportunity to engage with them directly. Measuring 55 x 38 cm, Cantrill’s book was a sizeable (though lightweight) object; as such, it was not a guidebook. It was almost certainly intended to be looked at in a library or perhaps on a drawing room table, conjuring up a vision (or memory) of the gallery’s interior that was quite different from the experience that a viewer would have in person. I will now consider how the pictures Cantrill chose for his book were displayed in the physical space of the gallery from which they were drawn, and how the relationship between book and gallery might have inflected the reception and interpretation of these six pictures.

All six of the pictures in Cantrill’s catalogue were hung in the Old Gallery at Cleveland House, the room that came last on the route prescribed for visitors. The collection was exhibited in a series of rooms organized by schools; the route, which began in the New Gallery, gave precedence to the venerated pictures from Lower and Upper Italy, upon which Cleveland House’s reputation rested, followed by the French, Spanish, British, and Netherlandish schools. Following the plan provided in Britton’s catalogue (fig. 1), visitors were directed up the grand staircase and then immediately into the three rooms holding the great Italian pictures, namely the New Gallery, the Drawing Room, and the Dining Room. Visitors then retraced their steps back through the New Gallery and into an anteroom, hung with a few select paintings from the British school. Finally, at the end of the route, visitors arrived in the Old Gallery, densely hung with the “Northern Schools”, a capacious category comprising Belgian, Dutch, Flemish, and German painters.

Figure 11.

John Roffe (engr.), Old Gallery, in William Young Ottley, Engravings of the Most Noble the Marquis of Stafford’s Collection of Pictures in London (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown, 1818), 61 cm

Digital image courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut

A detailed plan of the Old Gallery published in 1818 (fig. 10) permits a reconstruction of the hanging locations of many of the pictures on display at this date, including all of those in Cantrill’s book. Inherent in the small size and elaborate detail of genre pictures was the notion that they should be viewed up-close and intimately. At Cleveland House, the art-historical structure that was imposed on the hanging meant the most prominent locations were reserved for the larger pictures—thus, the Old Gallery was dominated by a large allegorical painting by Rubens, Peace and War, which was centred over the mauve upholstered sofa on the left-hand wall, where it could be easily seen from all angles. In contrast, many of the smaller pictures were hung high above doors and in remote corners; the smaller pictures were often well above a viewer’s eye-line. Overall, the small sizes of the pictures and their sheer number created a richly patterned wall surface which visually subsumed individual paintings. Teniers’s Farm Houses and Boors hung over a passage door leading from the far end of the Old Gallery into the Library, a room excluded from the gallery route; similarly, Teniers’s Boors Playing Cards was hung well above eye-level on the right-hand wall, below a much larger picture of a Dutch festival by a much lesser-known painter, Cornelius Molinaer. Le Nain’s tiny Village Piper was situated on a supporting column at the lower left-hand side of the plan, which illustrates its obscured position by way of a thin gold rectangle representing its frame as seen from the side. Brekelenkam’s Returning Thanks hung on the opposite column, near Fyt’s Starving Dog, which was very high on the wall at the right-hand side of the plan. Teniers’s Ducks in the Water was hung above a table on one side of the entrance to the Old Gallery, depicted at the bottom of the plan; it would have been to a visitor’s back as he or she entered the room.

The location of northern genre pictures at the end of the gallery route marked them as lesser in significance, more understandable, and more relatable to daily life than the grandiose mythological and historical subjects that preceded them. John Britton’s 1808 guidebook had largely dismissed the “Northern Schools” as works which did not offer much beyond “commonplace objects, and vulgar personages”.36 Even as pictures featuring “low” subject matter, particularly those by Teniers, became sought after in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, they continued to occupy an ambiguous place on the walls of upper-class interiors. The vulgarity of these pictures, while part of their appeal, presented particular challenges when displaying art in a gallery purporting to elevate the taste of the public, as Cleveland House did. In 1808, for example, Humphry Repton, in reviewing a picture by Adriaen von Ostade, remarked on its unsuitability for the polite audiences who frequented Cleveland House (it featured a lawyer using his spittoon); Repton wrote that it was “in no respect inferior [but] seems to have been placed in an obscure corner for reasons perfectly consonant to our notions of delicacy: it is, therefore, seldom seen, and often only glanced at and avoided by the ladies who visit this gallery”.37 As Repton’s comment implies, the role that northern paintings played within the gallery’s art-historical narrative could come into tension with their visual coarseness, an issue addressed by hanging such pictures in less visible locations. Fyt’s Starving Dog, for example, hung quite high on the wall, was likely placed there in order to prevent visitors from being forced to confront its upsetting subject matter too directly.

At the same time, genre pictures featured homely subjects and naturalistic technique that invited not only close looking, but expressions of emotion on behalf of the figures they depicted, and were sometimes displayed to accommodate this type of viewing. In June 1806, fifteen-year-old Frances Waddington witnessed such a public display of feeling when the renowned actress Mrs Siddons visited the gallery: “At length she picked out a painting of some Dutch fishwomen, the last thing upon earth you could call interesting, and ‘what a sweet composition is that!’ was pronounced in her deepest tragedy tones.”38 Waddington cannily understood that Siddons was using the picture to perform her skills as a dramatic actress, but her encounter with Siddons also demonstrates how privileged gallery visitors might draw upon the pictures’ “common” subject matter to enact their understanding of the way of life portrayed and exhibit their sympathetic reaction to it.39 While the pictures in question had not necessarily been painted with a moralizing message embedded into them, the personal interactions taking place in the gallery permitted such sympathetic and moralizing messages to emerge in the context of a society in which the personal expression of “sensibility” had become desirable.40 Cantrill’s catalogue enables such displays of sensibility by placing an exclusive emphasis on such “vulgar personages”, permitting viewers to engage with them directly and intimately, often in direct contrast to the way the same pictures were presented out of convenient viewing distance on the gallery walls. The catalogue’s focus on scenes of village life suggests that the selection was calculated to permit sustained consideration of the images and, on occasion, empathy with the downtrodden figures they represented. The framework for viewing pictures that Cantrill’s book provided ensured that they would be explicitly associated with the name of the Marchioness of Stafford, and is emblematic of the relationship the Marchioness wished to maintain with her tenants and employees—one in which they saw each other eye to eye, but with a full understanding of the differences that lay between them.

Conclusion

The controversy over the Staffords’ handling of their Sutherland estates was not yet over by the time Cantrill’s book appeared, and indeed was to worsen (in 1815, one of the Stafford’s employees was put on trial for murder after a cottage eviction went disastrously wrong).41 As Eric Richards has demonstrated, both the Marquess and Marchioness were keen to manage their family’s reputation through recourse to the press; by 1808 the estate was already issuing “flat denials” to critical reports in Scottish newspapers.42 The censorious comments further circulated through rumour and gossip in the Marchioness of Stafford’s social circles. In private correspondence, she took steps to rebut the accusations, writing to one acquaintance:

We have lately been much attacked in the newspapers by a few malicious writers who have long assailed us on every occasion. What is stated is most perfectly unjust and unfounded, as I am convinced from the facts I am acquainted with, and I venture to trouble you with the enclosed . . . If you meet with discussions on the subject in Society, I shall be glad if you will show this statement to anyone who may interest him or herself on the subject.43

Cantrill’s book can be interpreted as one shot fired in the battle over reputation taking place during these eventful years. An appeal to the collection offered an ideal way to change the subject, from the controversy surrounding land management to the family’s most visible and admired contribution to the public good: the gallery at Cleveland House. From the evidence that survives, a few crucial hints as to the book’s intended audience and possible use may be gleaned. Cantrill’s catalogue is precisely the type of object that might circulate within the intimate circles of a family—it could function as a memento honouring the lady of the house, while wordlessly reminding the reader of her beneficence as an employer, patroness, and benefactress of the arts. Cantrill’s book was privately printed; few copies survive in public collections, suggesting that unlike other catalogues it was intended for circulation amongst a small, hand-picked audience. The copy reproduced here was presented to the Society of Antiquaries in London by Revd Henry John Todd, who had a distant, but personal, connection to the Marquess and Marchioness, having served as the private chaplain to the 7th Earl of Bridgewater, a cousin of the late Duke of Bridgewater whose collections formed the Cleveland House gallery’s core.44 The title page bears a price, 12s., and indicates it could be purchased at a number of booksellers, including Ackermann, Colnaghi, and Molteno. Yet, the scarcity of copies in public collections (the Society of Antiquaries and the British Museum are the only two I have located) suggests that it did not circulate widely; its audience was probably primarily family and friends.

From its dedication, which positions the collection as the personal domain of the Marchioness, to its final image, associating her with the domestic morality betokened by its subject, Cantrill’s book presents a way of thinking about the gallery and its purpose that runs counter to the public virtues that the gallery had elsewhere been used to promote. As noted above, most catalogues, like those by Britton and Ottley, focused on the Marquess of Stafford’s patriotic and noble example, a gentleman enacting his duty to the nation in making his collection accessible to the public; Cantrill’s is dedicated exclusively to the Marchioness. The Sutherland estates were her ancestral property, and it was she who bore the dual titles of Marchioness of Stafford and Countess of Sutherland. This shift in focus to the Marchioness allows the book to appeal to its audience along traditionally gendered lines, linking the collection to the feminine (and private) virtues of domesticity and conscientious household management. The “humble” dedication from a “grateful and dutiful servant”, emphasizes this personal, domestic connection between author and dedicatee, offering the series of etchings it contains as a token of devotion, supporting the notion that the bond between aristocrat and dependant had not been as completely broken as events in the Highlands might suggest. Of course, nowhere does Cantrill’s catalogue directly mention the unrest on the Marquess and Marchioness’s Scottish estates; on the contrary, it implies an easy and naturally ordered relationship between the Marchioness and her dependants. In doing so, it presents the relationship between mistress and servant as one which is mutually beneficial while remaining appropriately deferential. An appeal to the subjects of common life also disassociated the Marchioness of Stafford from the Continental and sensual Italianate pictures which gave Cleveland House its reputation.45 Although the pictures chosen were somewhat incongruously associated with “vulgar” subjects which might have been unsuitable for dedication to a female patron, the choice of imagery emphasizing an easily comprehensible social order allows Cantrill’s offering to the Marchioness to be interpreted as a validation of her authority and actions as a mistress and landowner. By extension, it associates the grand public space of Cleveland House’s gallery with a private and moral sensibility.

The celebration of Cleveland House as a “national museum” suggests that the art for which it was famed, in particular the works of Italian Renaissance masters, could be understood as an overarching culture that included all citizens of the nation, from London to the furthest reaches of Scotland and Wales; from townhouse to cottage. This catalogue’s presentation as a token of affection from an “untutored” porter to one of the richest and most dazzling aristocratic hostesses of the age implies a symbiosis between the aristocracy who collected pictures and the tenantry whose work enabled such collecting. However, in practice, the bringing together of the various parts of Britain under one cultural umbrella was a fractured process, one which the Marquess and Marchioness of Stafford’s far-flung personal empire demonstrates. The geographical and cultural divide separating the rural estate from urban life could be difficult to reconcile, and the notion that the “national” culture being forged in the Cleveland House gallery was truly intended for a seamlessly integrated Great British public is self-evidently problematic. The people living on the Marquess and Marchioness’s Scottish (and English, for that matter) estates were not part of the public for the gallery—their humble cottages were the obverse to the glamorous and urbane life the family enjoyed in London. The Marquess and Marchioness belonged to an aristocracy whose cultural and political authority superseded such national designations in a way their tenants never could. Cantrill’s catalogue, through the deployment of scenes of everyday life, glosses over the conflicts which had arisen between the Marquess and Marchioness of Stafford and their tenants, and promotes an aura of private morality in a space which was reported in the papers as a semi-public institution of national, and even international, significance. Subject pictures, as deployed in Cantrill’s catalogue, offered upper-class audiences an alternative and comforting vision of the “national” culture being constructed in the Cleveland House gallery through the frame of common life.

Footnotes

-

Press-cuttings, from English newspapers . . . National Art Library, Victoria & Albert Museum, London (Shelfmark P.P.17.G), 578 (1790). The Orleans Collection (written without an accent in English) was a collection of old master paintings belonging to Louis-Philippe, Duc d’Orléans, which had been imported into Britain during the 1790s in the aftermath of the French Revolution and sold to British collectors. The best Italian and French pictures from the Orleans Collection were purchased by a group of collectors called the Bridgewater consortium, led by Francis Egerton, the 3rd Duke of Bridgewater. The Marquess of Stafford, the Duke’s nephew, was invited to join the consortium along with his cousin, the Earl of Carlisle. The Duke of Bridgewater died in 1803 and left his portion of the Orleans pictures and Cleveland House to the Marquess of Stafford. A recent and invaluable article by Peter Humfrey elaborates upon the 3rd Duke of Bridgewater’s collecting practice in areas like Dutch painting. Humfrey, “The 3rd Duke of Bridgewater as a Collector of Old Master Paintings”, Journal of the History of Collections 27, no. 2 (2015): 211–25. For a detailed account of the Orleans Collection and its importation to England, see Nicholas Penny, The Sixteenth Century Italian Paintings, vol. 2, Venice, 1540–1600 (London: National Gallery, 2008), 461–70. Other important sources on the art market in this period include William Buchanan, Memoirs of Painting, with a Chronological History of the Importation of Pictures of the Great Masters into England since the French Revolution (London: R. Ackermann, 1824); Gerald Reitlinger, The Economics of Taste: The Rise and Fall of the Picture Market, 1760–1960 (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1961), 26–38; Francis Haskell, The Ephemeral Museum: Old Master Paintings and the Rise of the Art Exhibition (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2000), 22–29; Jordana Pomeroy, “The Orleans Collection: Its Impact on the British Art World”, Apollo 145 (1997): 26–31; and Pomeroy, “Conversing with History: The Orléans Collection Arrives in Britain”, in British Models of Art Collecting and the American Response: Reflections Across the Pond, ed. Inge Reist (Farnham and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2014), 47–60.

1 -

A recent article by Peter Humfrey details the Marquess of Stafford’s practices as a collector and the relationship of his activities to the gallery at Cleveland House. Humfrey, “The Stafford Gallery at Cleveland House and the 2nd Marquess of Stafford as a Collector”, Journal of the History of Collections 28, no. 1 (2016): 43–55.

2 -

Richard Rush, Memoranda of a Residence at the Court of London (Philadelphia: Key and Biddle, 1833), 155.

3 -

John Britton, Catalogue Raisonné of the Pictures Belonging to the Most Honourable the Marquis of Stafford, in the Gallery of Cleveland House (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1808), and William Young Ottley, Engravings of the Most Noble the Marquis of Stafford’s Collection of Pictures in London, arranged according to Schools, and in Chronological Order, with Remarks on Each Picture (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1818). Britton and Ottley were the two most widely circulated catalogues but there are several others. The earliest, A Catalogue of Pictures at Cleveland-House (London: J. Hays, 1806), is a simple picture list that was likely used as a guidebook for gallery visitors. In 1807 the architect George Perry published A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Collection of the Marquis of Stafford in London (London: J. Walker, 1807), which departs from the pattern mentioned above by focusing on the British and Netherlandish pictures, but it appears to have enjoyed very limited circulation in contrast to Britton’s and Ottley’s efforts. Another picture list appeared in 1814 with the title Catalogue of the Pictures belonging to the Marquis of Stafford, at Cleveland House (London: M. Gummow, 1814). The last publication exclusively devoted to Cleveland House and its collection was John Young’s A Catalogue of the Collection of Pictures of the Most Noble The Marquess of Stafford at Cleveland House, London (London: Hurst, Robinson and Co., 1825).

4 -

Advertisement found in Press-cuttings, from English newspapers . . . National Art Library, Victoria & Albert Museum, London (Shelfmark P.P.17.G), 814. Probably because there were few who could afford such an expensive production, Ottley failed to achieve a return on his investment and went bankrupt.

5 -

On French catalogues in the eighteenth century, see Benedict Leca, “An Art Book and its Viewers: The ‘Recueil Crozat’ and the Uses of Reproductive Engraving”, Eighteenth-Century Studies 38, no. 4 (2005): 623–49. For guidebooks to collections in later eighteenth-century English houses, see Jocelyn Anderson, “Remaking the Space: The Plan and the Route in Country-House Guidebooks from 1770 to 1815”, Architectural History 54 (2011): 195–212.

6 -

Britton, Catalogue Raisonné, vii.

7 -

[W. Cantrill], Etchings from Original Pictures in the Cleveland-House Gallery, drawn, etched, and dedicated to the Marchioness of Stafford, by her Ladyship’s Porter (London: Published by subscription, Price 12s., 1812). Many thanks to Charles Sebag-Montefiore for arranging access to the library of the Society of Antiquaries so that I could examine this book.

8 -

David Solkin, Painting Out of the Ordinary: Modernity and the Art of Everyday Life in Early Nineteenth-century Britain (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2008), 2. On the popularity of Netherlandish genre scenes amongst early nineteenth-century collectors, see also Harry Mount, “‘Our British Teniers’: David Wilkie and the Heritage of Netherlandish Art”, in David Wilkie: Painter of Everyday Life, ed. Nicholas Tromans (London: Dulwich Picture Gallery, 2002), 30–39, and Harry Mount, “The Reception of Dutch Genre Painting in England, 1695–1829”(D.Phil. diss, University of Cambridge, 1991).

9 -

Robert Southey, Journal of a Tour in Scotland in 1819, ed. C. H. Herford (London: John Murray, 1929), 136.

10 -

Marx described the clearances as the “transformation [of land] into modern private property under circumstances of reckless terrorism”. Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, ed. Frederick Engels (New York: Modern Library, 1906), 805.

11 -

John Prebble, The Highland Clearances (London: Secker & Warburg, 1963).

12 -

The historian Eric Richards’s enormous body of writing on this topic provides an even-handed scholarly treatment, and has provided an important foundation for the discussion of agricultural policy found in this article. In general Richards argues that an unbiased interpretation of these events suggests that the actions of landlords were often heavy-handed, but that charges of racial animosity toward the Highlanders are overstated. See Eric Richards, The Leviathan of Wealth: The Sutherland Fortune in the Industrial Revolution (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973); Richards, A History of the Highland Clearances: Agrarian Transformation and the Evictions, 1746–1886 (London: Croom Helm, 1982); Richards, Patrick Sellar and the Highland Clearances: Homicide, Eviction and the Price of Progress (Edinburgh: Polygon, 1999); and Richards, The Highland Clearances: People, Landlords, and Rural Turmoil (Edinburgh: Berlinn, 2000).

13 -

Prebble was one of the few to draw any connection between these events. He alleges, for example, that the £3,000 Stafford spent on a picture by Rubens from the Doria Palace in Genoa, was a sum amounting to fully half of what he spent on poor relief during one typhus epidemic in the Highlands. He makes the point for its highly emotional impact on the reader, but presses the comparison no further. Prebble, Highland Clearances, 60.

14 -

Turner’s Dutch Boats in a Gale, also known as “The Bridgewater Seapiece”, was amongst those works the Marquess of Stafford inherited, and was displayed alongside other pictures from the English school at Cleveland House. Martin Butlin and Evelyn Joll, The Paintings of J. M. W. Turner (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1984), 12–13, cat. no. 14.

15 -

To date, Giles Waterfield has done the most extensive work on the London townhouse collection, and I am indebted to his work. See especially Waterfield, ed., Palaces of Art: Art Galleries in Britain, 1790–1990 (London: Dulwich Picture Gallery, 1991), and Waterfield, “The Town House as Gallery of Art”, London Journal 20, no. 1 (1995): 47–66.

16 -

Quoted in William Thomas Whitley, Art in England, 1800–1820, 2 vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1928), 1:109.

17 -

“Monthly Retrospective of the Fine Arts”, Monthly Magazine and British Register 21 (July 1806): 543–46.

18 -

“Funeral of the Duke of Sutherland. July 31st 1833”, Inverness Courier, 7 Aug. 1833. In file of clippings on the death of the Duke of Sutherland. National Library of Scotland, Sutherland archive, Dep. 313 [798].

19 -

Southey, Journal, 136.

20 -

She also held the ancient title Great Lady of Sutherland—in Gaelic, Ban mhorair Chataibh. Prebble, Highland Clearances, 59. Elizabeth inherited the Sutherland estate and its associated benefits and responsibilities after her parents died in 1766 when she was not yet two years old. During her minority the estates were managed by a board of Tutors, but by her eighteenth birthday she had begun actively participating in their management.

21 -

The poverty of Sutherland also contrasted sharply with the modernity and prosperity associated with the Marquess of Stafford’s properties in Staffordshire. The Leveson-Gower family’s holdings in Staffordshire had increased significantly in value during the latter part of the eighteenth century due to the construction of the Duke of Bridgewater’s canal network and from the related processes of industrialization. Richards writes that after the marriage of the Marquess and Marchioness of Stafford, “the most unmodernised remote corner of the British Isles became interlocked with the most dynamic sector of its most advanced region—Lancashire and the West Midlands.” Richards, Patrick Sellar, 38.

22 -

See Anne Janowitz, “Land”, in An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age, ed. John Mee, Gillian Russell, and others (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1999), 155.

23 -

B.G. [?], “On the Condition of the Highland Peasantry Before and Since the Rebellion of 1745”, New Monthly Magazine and Universal Register 11, no. 66 (1 July 1819): 504–9.

24 -

Thomas Bakewell, Remarks on a Publication by James Loch, Esq. (London: Longman, 1820), 38.

25 -

This is the only painting from Cantrill’s catalogue that is now in a public collection.

26 -

Porter is a term derived from French for a doorman, doorkeeper, or gatekeeper (see “porter, n.1.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2016). Some confusion may arise from the fact that there were two types of porters in London of this period, the type working as a doorkeeper in a private house and the more common type, who were unskilled labourers worked on the wharves and in other places around the city transporting cargo. While few scholars have investigated the role of the porter within the household specifically, Peter Earle’s A City Full of People: Men and Women of London, 1650–1750 (London: Methuen, 1994) provides valuable background information. A few scholars have addressed the cultural significance of doors and doorways in the London house, see for example Amanda Vickery, Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2009), 25–48.

27 -

Britton, Catalogue Raisonné, unpaginated; #xz “Regulations”.

28 -

Monks is speaking specifically of the work of Van de Velde here, but her point holds more generally. Sarah Monks, “Turner Goes Dutch”, in Turner and the Masters, ed. David Solkin (London: Tate, 2009), 74.

29 -

Britton, Catalogue Raisonné, 120.

30 -

Identified in Britton, Catalogue Raisonné, 138, as “A Dog chained”.

31 -

First-hand accounts vividly describe the evictions undertaken by the Marquess and Marchioness’s representatives although they must be treated with caution, since most were not recorded until many years later. This quote from Betsy Mackay refers to events that took place in 1814, but is itself undated, and is quoted in Prebble, Highland Clearances, 87.

32 -

In Britton, Catalogue Raisonné, 135, this painting is identified as no. 200, “Dutchmen Playing at Nine-Pins”.

33 -

Solkin, Painting Out of the Ordinary, 40.

34 -

Wayne Franits, Dutch Seventeenth-century Genre Painting: Its Stylistic and Thematic Evolution (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2004), 131. Small in size, such pictures originally sold for modest sums and would have been understood by Brekelenkam’s clients as images of piety and the spiritual wisdom that was a positive benefit of old age. By the early nineteenth century, such images surely had lost much of the delicate web of meanings that attached to them in their original context. Franits, 74–75, 130–34.

35 -

Britton, Catalogue Raisonné, 117.

36 -

Repton, in Britton, Catalogue Raisonné, 146.

37 -

Letter dated 23 June 1806. Augustus J. C. Hare, The Life and Letters of Frances, Baroness Bunsen (London: Daldy, Isbister and Co., 1879), 1:75.

38 -

Siddons herself could also become an object of scrutiny in the context of public exhibitions, in ways that enhanced her reputation as an actress but also called into question her claims to morally upstanding forms of femininity. See Gill Perry, “The Spectacle of the Muse: Exhibiting the Actress at the Royal Academy”, in Art on the Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836, ed. David Solkin (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2001), 111–25.

39 -

On the use of contemporary painting based on Dutch genre scenes for an expression of concepts of charity, see Georgina Cole’s “‘A beautiful assemblage of an interesting nature’: Gainsborough’s Charity Relieving Distress and the Reconciliation of High and Low Art”, British Art Studies 1 (Nov. 2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-01/gcole

40 -

For an account of the trial of Patrick Sellar, which took place in April 1816 in Inverness, see Richards, Patrick Sellar, 182–223.

41 -

Richards, Patrick Sellar, 45.

42 -

Quoted in Prebble, Highland Clearances, 112–13.

43 -

See D. A. Brunton, “Todd, Henry John”, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2004).

44 -

See Philippa Simpson’s recent work, which examines how the sensual content of many of the Italian masters was received. Simpson, “Titian in Post-Orleans London”, in The Reception of Titian in Britain: From Reynolds to Ruskin, ed. Peter Humfrey (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013), 99–108.

45

Bibliography

Anderson, Jocelyn. “Remaking the Space: The Plan and the Route in Country-House Guidebooks from 1770 to 1815.” Architectural History 54 (2011): 195–212.

B.G. [?] “On the Condition of the Highland Peasantry Before and Since the Rebellion of 1745.” New Monthly Magazine and Universal Register 11, no. 66 (1 July 1819): 504–9.

Bakewell, Thomas. Remarks on a Publication by James Loch, Esq. London: Longman, 1820.

Britton, John. Catalogue Raisonné of the Pictures Belonging to the Most Honourable the Marquis of Stafford, in the Gallery of Cleveland House. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1808.

Brunton, D. A. “Todd, Henry John.” In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2004.

Buchanan, William. Memoirs of Painting, with a Chronological History of the Importation of Pictures of the Great Masters into England since the French Revolution. London: R. Ackermann, 1824.

Butlin, Martin, and Evelyn Joll. The Paintings of J. M. W. Turner. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1984.

[Cantrill, W.] Etchings from Original Pictures in the Cleveland-House Gallery, drawn, etched, and dedicated to the Marchioness of Stafford, by her Ladyship’s Porter. London: Published by subscription, 1812.

Catalogue of the Pictures belonging to the Marquis of Stafford, at Cleveland House. London: M. Gummow, 1814.

Cole, Georgina. “‘A beautiful assemblage of an interesting nature’: Gainsborough’s Charity Relieving Distress and the Reconciliation of High and Low Art.” British Art Studies 1 (Nov. 2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-01/gcole

Earle, Peter. A City Full of People: Men and Women of London, 1650–1750. London: Methuen, 1994.

Franits, Wayne. Dutch Seventeenth-century Genre Painting: Its Stylistic and Thematic Evolution. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2004.

“Funeral of the Duke of Sutherland. July 31st 1833.” Inverness Courier, 7 Aug. 1833. National Library of Scotland, Sutherland archive, Dep. 313 [798].

Hare, Augustus J. C. The Life and Letters of Frances, Baroness Bunsen. London: Daldy, Isbister and Co., 1879.

Haskell, Francis. The Ephemeral Museum: Old Master Paintings and the Rise of the Art Exhibition. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2000.

Humfrey, Peter. “The 3rd Duke of Bridgewater as a Collector of Old Master Paintings.” Journal of the History of Collections 27, no. 2 (2015): 211–25.

– – –. “The Stafford Gallery at Cleveland House and the 2nd Marquess of Stafford as a Collector.” Journal of the History of Collections 28, no. 1 (2016): 43–55.

Jameson, Anna. Companion to the Most Celebrated Private Galleries of Art in London. London: Saunders and Otley, 1844.

Janowitz, Anne. “Land.” In Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age. Ed. John Mee, Gillian Russell, and others. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1999, 15.

Leca, Benedict. “An Art Book and its Viewers: The ‘Recueil Crozat’ and the Uses of Reproductive Engraving.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 38, no. 4 (2005): 623–49.

Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Ed. Frederick Engels. New York: Modern Library, 1906.

Monks, Sarah. “Turner Goes Dutch.” In Turner and the Masters. Ed. David Solkin. London: Tate, 2009, 73–85.

“Monthly Retrospective of the Fine Arts.” Monthly Magazine and British Register 21 (July 1806).

Mount, Harry. “‘Our British Teniers’: David Wilkie and the Heritage of Netherlandish Art.” In David Wilkie: Painter of Everyday Life. Ed. Nicholas Tromans. London: Dulwich Picture Gallery, 2002, 30–39.

– – –. “The Reception of Dutch Genre Painting in England, 1695–1829.” D.Phil. diss., University of Cambridge, 1991.

Ottley, William Young. Engravings of the Most Noble the Marquis of Stafford’s Collection of Pictures in London, arranged according to Schools, and in Chronological Order, with Remarks on Each Picture. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1818.

Penny, Nicholas. The Sixteenth Century Italian Paintings, vol. 2, Venice, 1540–1600. London: National Gallery, 2008.

Perry, George. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Collection of the Marquis of Stafford in London. London: J. Walker, 1807.

Perry, Gill. “The Spectacle of the Muse: Exhibiting the Actress at the Royal Academy.” In Art on the Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836. Ed. David Solkin. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2001, 111–25.

Press-cuttings, from English newspapers . . . National Art Library, Victoria & Albert Museum, London (Shelfmark P.P.17.G).

Pomeroy, Jordana. “Conversing with History: The Orléans Collection Arrives in Britain.” In British Models of Art Collecting and the American Response: Reflections Across the Pond. Ed. Inge Reist. Farnham and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2014, 47–60.

– – –. “The Orleans Collection: Its impact on the British Art World.” Apollo 145 (1997): 26–31.

Prebble, John. The Highland Clearances. London: Secker & Warburg, 1963.

Reitlinger, Gerald. The Economics of Taste: The Rise and Fall of the Picture Market, 1760–1960. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1961.

Richards, Eric. A History of the Highland Clearances: Agrarian Transformation and the Evictions, 1746–1886. London: Croom Helm, 1982.

– – –. The Highland Clearances: People, Landlords, and Rural Turmoil. Edinburgh: Berlinn, 2000.

– – –. The Leviathan of Wealth: The Sutherland Fortune in the Industrial Revolution. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973.

– – –. Patrick Sellar and the Highland Clearances: Homicide, Eviction and the Price of Progress. Edinburgh: Polygon, 1999.

Rush, Richard. Memoranda of a Residence at the Court of London. Philadelphia: Key and Biddle, 1833.

Simpson, Philippa. “Titian in Post-Orleans London.” In The Reception of Titian in Britain: From Reynolds to Ruskin. Ed. Peter Humfrey. Turnhout: Brepols, 2013, 99–108.

Southey, Robert. Journal of a Tour in Scotland in 1819. Ed. C. H. Herford. London: John Murray, 1929.

Solkin, David. Painting Out of the Ordinary: Modernity and the Art of Everyday Life in Early Nineteenth-century Britain. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2008.

Vickery, Amanda. Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2009.

Waterfield, Giles. “The Town House as Gallery of Art.” London Journal 20, no. 1 (1995): 47–66.

Waterfield, Giles, ed. Palaces of Art: Art Galleries in Britain, 1790–1990. London: Dulwich Picture Gallery, 1991

Young, John. A Catalogue of the Collection of Pictures of the Most Noble The Marquess of Stafford at Cleveland House, London. London: Hurst, Robinson and Co., 1825.